Commentary: Always Know What to Say

Welcome to the background commentary and recommended reading for the “Always Know What to Say” mental model and the “Making Marketing Messages” framework exercise.

Welcome to the background commentary and recommended reading for the “Always Know What to Say” mental model and the “Marketing Message Maker” framework exercise.

A note on format: Commentary issues contain recommended reading and quotes I found useful in my work, loosely connected by my commentary.

One of the concepts that struck me most in David C. Baker’s superbly succinct The Business of Expertise is his explanation of why everyone struggles to promote their business:

“The project that’s been on the Monday morning job sheet the longest is the development company’s own website, not because they don’t know how to build great websites but because they don’t know what to say.”

Ditto every marketing company’s marketing strategy.

This inability to say something meaningful accelerates the unwitting race to commoditization—because saying something meaningful means being specific, and being specific means focus. And focus means saying no.

And that’s hardest thing of all to say.

But some of the psychic weight comes off when we start looking for messaging principles to guide us, instead of methods and tactics:

Potentially the world’s most prolific voice on the utility of mental models, Shane Parrish, quotes “scientific management” theorist Harrington Emerson in his Great Mental Models Volume 1, saying:

“As to methods, there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The [person] who grasps principles can successfully select [their] own methods. The [person] who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.”

You already know plenty of marketing and “lead generation” tactics, and every spammer in your LinkedIn DMs is willing to sell them to you for a penny.

But that’s all they're selling you: spam. Meaningless, untargeted, awareness-focused messages hoping to attract enough attention that someone will accidentally buy.

No, the point isn’t to reach as many people as possible and hope for the best.

It’s to reach as many of the best possible people. Hope has less work to do when you stack the odds in your favor.

Claude C. Hopkins, probably the most influential advertising copywriter of all time, once wrote, “There I learned another valuable principle in advertising. In a wide-reaching campaign we are too apt to regard people in the mass. We try to broadcast our seed in the hope that some part will take root. We must get down to individuals. We must treat people in advertising as we treat them in person. Center on their desires. Consider the person who stands before you.”

That’s what positioning is. It’s about positioning your business and your marketing to operate in the same mindspace as your customer, at their moment of greatest need.

How?

As April Dunford, writer of Obviously Awesome, the best book on positioning in almost 40 years, put it, “Positioning is the act of deliberately defining how you are the best at something that a defined market cares a lot about.”

But who cares? The people who value it.

But how do you know if they value it?

They show you:

“In everything you do, keep your eye glued to the heavy users. They are unlike occasional users in their motivations,” wrote midcentury “scientific advertising” acolyte David Ogilvy.

Too many businesses die on the long road to convincing people who don’t want to spend money to buy something they don’t need. It's only the quick road to misery.

Because marketing isn’t about convincing anybody of anything. It’s about helping people get what they want.

So who wants what you sell?

The people who already buy something like it, or who are “cobbling together a workaround solution involving multiple products,” as Clayton Christensen and his coauthors wrote in Competing Against Luck.

Those are the folks you’re targeting, but you’ve got to know more about what they actually need, so you can make the right tradeoffs to serve them best, while still running a profitable business.

“Customers don’t buy products or services,” Competing Against Luck continues, “they pull them into their lives to make progress. We called this progress the ‘job’ they are trying to get done, and in our metaphor we say the customers ‘hire’ products or services to solve these jobs.”

This is how we start shaping up our marketing position so we can create messages that matter. First, we identified our frequent and high-value customers (“heavy users,” in Ogvily’s words) who want the type of thing we offer. Then, we figured out the actual “job” or “progress” they’re trying to make, a la Christensen and company.

Next, we’ve got to figure out how we can be the best possible option for our ideal customer, without going broke before we finish the job.

Jennifer Riel and Roger Martin, in what’s become my most recommended book on strategic thinking, Creating Great Choices, remind us: “Integrative thinking isn't about ‘doing both’ but rather about finding an answer that takes the best of both to produce outcomes that are preferable to existing ones.”

The job isn’t to do everything—it’s to do only what needs to be done, the best way we know how, for the people who value it most. We ditch the rest by becoming so great at the single thing we do best that we don’t need to do anything else.

The next question, once we know Who needs us, What they need, and How we’re best suited to help in our singularly focused way, is When they need us.

Theodore Levitt is credited with the witty observation, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole.” Summarized by Christensen: “Customers don’t want products, they want solutions to their problems.”

But problems are timebound—they don’t exist until they do. There’s a moment when something goes from fine to not fine, and that’s when our customers need us most.

Bob Moesta describes it perfectly as the “Struggling Moment” in Demand-Side Sales 101: “You create pull for your product because you are focused on helping the customer. Demand-side selling starts with the struggling moment. It’s the theory that people buy when they have a struggling moment and think, ‘Maybe, I can do better.’”

That’s our customer’s moment of greatest need, and the moment we can be most useful, most valuable.

Knowing this gives us a lot of space and freedom to find customers where they are, rather than trying to create them out of thin air through futile “lead generation” tactics.

Like Moesta once said, “We don’t create demand, we uncover demand. The struggling moment creates demand.”

But there’s no use in having a When if we don’t have a Where. That is, where do your best customers go once they experience that moment of need?

Jonathan Stark of the Ditching Hourly and The Business of Authority podcasts, some of the most valuable contemporary resources on consulting, calls these places “watering holes.”

Forums, trade shows, conferences, subreddits, Discord servers, industry publications, referral networks—the places the type of people we work with best and who find us most valuable go when they talk about the kind of stuff they need or the kind of stuff we do.

But once you have that information, isn’t all the work still ahead of you? Isn’t the hard part writing about this? Making ads? Preparing pitches? Isn’t that the tough problem?

No, not really. It’s only tough if you haven’t done this work first.

If you have, as David Ogilvy said, all you have to do is “Tell the truth, and make it interesting.”

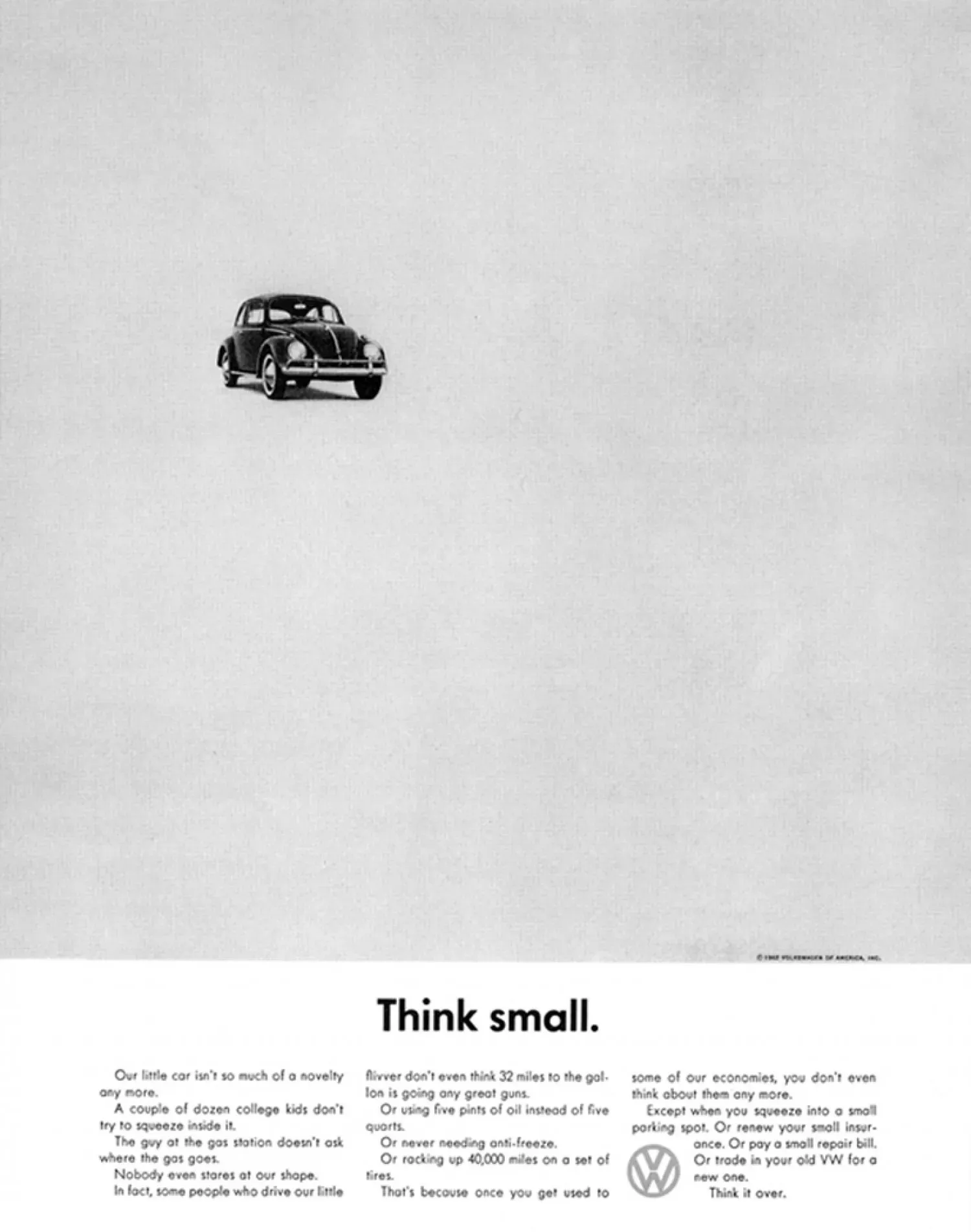

Bob Levenson, who wrote my favorite ad of all time, insisted it was all pretty easy:

“When you really don’t know what to put on that blank paper in the typewriter, you should just write ‘Dear Charlie’ at the top. Assume that Charlie is a neighbor of yours, a very nice, bright, intelligent guy, with a sense of humor. He’s got all the mental equipment you have, but none of the information that you have about the Volkswagen. So just put down what you want to tell him in this ad, and cross off ‘Dear Charlie’, and you’ll probably be all right.”

Write out your position, your Who, What, How, When, and Where.

Imagine how you could get a message in front of your Who at that Where, at that When.

Then, imagine how you could communicate to them How your solution is best suited for their particular What.

Write that down.

Try it out and, as Levenson says, “you’ll probably be all right.”