Concepts and Quotes: One Big Day

Last week was a fairly short piece on the “One Big Day” problem, with no quotes or external references. Today, here’s a dive into some of the ideas, models, and quotes that informed my thinking.

Last week was a fairly short piece on the “One Big Day” problem, with no quotes or external references.

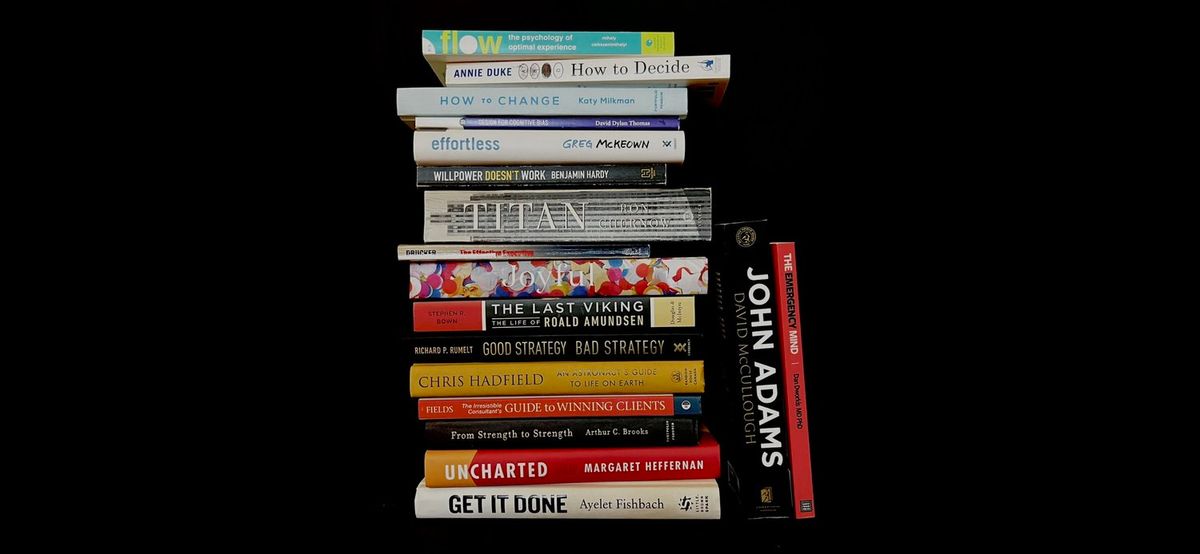

Today, here’s a dive into some of the ideas, models, and quotes that informed my thinking. The quotes and references are emphasized, my commentary is in plain text below each one. They’re organized by specific concept or category. Links are provided for online resources, titles and authors are provided for books.

Your Future Capacity:

In Arthur C. Brooks’ From Strength to Strength, he talks about the economic concept of “Stein’s Law.”: "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop."

So, if your plan for the future involves you doing something you can’t stick with, your plan will fail, eventually.

In Ayelet Fichbach’s Get It Done, she says, “Instead of asking yourself whether it's okay to procrastinate, cheat, smoke, or drink today, you should ask yourself whether it's okay to do so for the rest of your life.” Which means, “if you think a decision you make today is diagnostic of all future choices, you'd better make the right decision today.”

We can see the obviousness of this when it’s something clearly and objectively bad for us. But trying to pile too many plans, goals, or dreams onto our future self is also bad. When you make a plan for the future, you’ve got to think incredibly clearly about taking the necessary action every day, potentially forever.

And when we do eventually confront the largeness of the task, we tend to procrastinate because “you’ve visualized something for yourself in the future that your present level of capability and confidence can’t pull off,” according to Dan Sullivan in Procrastination Priority. “You’re simply making an accurate assessment of the gap between where you are now and where you want to be.”

If you’re procrastinating about something, it’s not because you’re lazy or because you’re a bad person. It’s because you don’t know what you’re supposed to do—or you don’t think you can actually do it. You’re going to fail at your resolution, plan, or goal if you’re not actually capable, ready, or supported enough to make it happen. So address those things first.

You can tell if you’re likely to fail at your resolution if you’re being advertised products to support New Years Resolutions. As David A. Fields wrote in The Irresistible Consultant’s Guide to Winning Clients, “Learn what clients have actually spent money on in the past, not what they say they’ll do in the future.”

If you’re someone who buys products, courses, or books to support New Years Resolutions, you’re likely to continue—not because they work, but expressly because they don’t. Stop doing the same things that don’t work and do something new. Even if it fails, you’re no worse off.

Margaret Heffernan brings it home in Uncharted: “Only if you concede that someone else owns your future are you truly trapped.”

You don’t have to keep failing at big goals. You just have to stop attempting them the same way. Your instincts are wrong, your impulses are misguided. Follow what works, not what feels right. Efficiency is unintuitive. But you don’t have to be trapped by convention or anxiety—you don’t have to concede that someone else (including your bad impulses) own your future.

So, you feel excited about your resolution, or your Annual Strategic Plan. Finally, it’s all in place, and it’s all going to come together. And then it’s Day One of implementation. Uh oh. It’s hard. It’s boring. It’s not exciting anymore at all. What happened?

“Psychological research has found that the anticipation of an event is almost always a more charged emotional experience than the event itself,” says Benjamin Hardy in Willpower Doesn’t Work.

The anticipation of success was exciting, the anticipation of action completely sucks.

But, “almost always,” Hardy continues, “you imagine it will be far worse than it ever really is. Then you extend that pain by procrastinating action. If you would just act, the pain would be far less severe and over before you know it.”

The future always looks alternately blue sky perfection or red sky apocalyptic. Neither’s likely to be correct.

Like that old saying, supposedly by Bismarck: “Life is like being at the dentist. You always think the worst is still to come, and yet it is already over.”

New Year’s Resolutions Don’t Work:

So, let’s face facts, “You're not alone in quickly breaking your New Year's resolution,” writes Annie Duke in How to Decide. “Within a week, 23% of New Year's resolutions are abandoned. And 92% of people never achieve their goal. When it comes to reaching our goals, we have an execution problem.”

Yikes. If that many people fail at something, it seems prudent to take a quick look at alternative paths, no?

It doesn’t matter how much we want to succeed if the actions we’re taking can’t work: “Evidence suggests that, surprisingly, our intentions are only loosely predictive of our behaviors,” writes Katy Milkman in How to Change.

Dan Sullivan, again in Procrastination Priority, says, “But what is procrastination? I’ve found that when it comes to procrastinating, ‘should’ tends to be the operative word.”

So one of the biggest problems is that we’re already starting from this place of obligation, which is unmotivating.

“Enthusiasm is incompatible with compulsion,” as B. H. Liddell Hart wrote in Why Don’t We Learn from History?

Worryingly, we might have to accept that making the resolution, and then making it public, and then failing, are serving us in some way.

As John Quincy Adams, as cited by David McCollough in John Adams, said about Congress, “This is now in general the great art of legislation at this place: To do a thing by assuming the appearance of preventing it. To prevent a thing by assuming that of doing it."

How many things are done on a daily basis to avoid doing the real thing? How many things end up happening simply because we did nothing to stop them? Resolutions fail because they were made to be made, not to be achieved.

And so the alternative is…

Pace and Fun:

First, my incredible business partner and wife Leah, who says, “If you can’t see the goal, set a pace.”

You’re not “sprinting” if you never plan to stop. You’re just burning out as fast as you can.

Endless exertion isn’t a sign of genius or strength, as Dan Dworkis wrote in The Emergency Mind. No, it’s the inexperienced leaders who “pace aimlessly while yelling orders to everyone indiscriminately or mumbling them to no one. They micromanage the small decisions while losing sight of the big ones, and try to overpower the uncertainty and pressure by simply ‘grinding through’ the problem.” Instead, “experienced emergency providers” do things “entirely differently.” For them, their “strategies are built not on taking more actions, but on slowing down to identify and then execute only the best possible actions for that patient in that moment.”

If emergency medicine experts know you should slow down, think things through, and take fewer actions when things get dicey in the hospital… maybe I should slow down a bit in my work where the stakes are, shall we say, appreciably lower.

The explorer Roald Amundsen said it’s vital that you don’t overexert yourself if you’ve got important work to do. This passage from Stephen R. Bown’s, The Last Viking, makes it plain: “‘If one is tired and slack,’" [Amundsen] mused, ‘it may easily happen that one puts off for tomorrow what ought to be done today; especially when it is bitter and cold.’ Light and simple were his benchmarks, ‘and that plays a not unimportant role on a long journey.’"

Part of the problem, though, is that we want to rush through difficult and big tasks. They’re important, and so they seem boring or terrifying.

I initially learned about Amundsen from a podcast interview I listened to with Greg McKeown, promoting his book Effortless. In in, he diagnoses why we put off or phone in our essential but difficult activities: “Believing essential activities are, almost by definition, tedious, we are more likely to put them off or avoid them completely. At the same time, our nagging guilt about all the essential work we could be doing instead sucks all the joy out of otherwise enjoyable experiences. Fun becomes ‘the dark playground.’ Separating important work from play makes life harder than it needs to be.”

It turns out, if you decide that your work is important enough to do right, that means it’s important enough to make fun. Because fun is what makes tedious things engaging, hard things challenging. Ambitious things achievable.

“Effective executives,” Peter Drucker wrote in The Effective Executive, “do not race. They set an easy pace but keep going steadily.”

The people who seem haggard and desperate on LinkedIn and TikTok keep telling me to hustle harder. But the people who seem to actually get stuff done, consistently and sustainably, keep telling me to slow the hell down and think more, and do less. Huh.

Of course we’ve got to take the words of reputation-obsessed robber barons with more than a grain of salt, but this quote from John D. Rockefeller in Ron Chernow’s Titan maps with everything else I’ve read and experienced: “It is remarkable how much we all could do if we avoid hustling, and go along at an even pace and keep from attempting too much.”

Speaking of…

Recovery and Rest:

In McKeown’s Effortless, he writes, “Studies show that peak physical and mental performance requires a rhythm of exerting and renewing energy—and not just for athletes. … Those who took fewer or shorter breaks performed less well.” And then, one of my very favorite directives: “Do not do more today than you can completely recover from today. Do not do more this week than you can completely recover from this week.”

It’s such a simple statement with such profound consequences. What does it mean to recover from the hard work I do? How much recovery would that mean if I met this dictum? How little recovery does that suggest I’m doing now?

But the need is real. Hardy, in Willpower Doesn’t Work: “Despite weighing only three pounds, your brain sucks over 20 percent of your body's energy. You really have only four or five good hours of mental focus per day. If you work effectively, your work should take on the form of deliberate practice, where you're doing 90- to 120-minute power sessions, followed by 20 to 30 minutes of recovery in a different environment.”

I would really, really like to think I’m using my brain effectively when I’m doing deep work. So, if I’m not drinking lots of water and taking lots of breaks, I’m either not actually doing deep work or I’m doing it poorly. Less than ideal.

But the voices creep in. How lazy. How luxurious. How unbusiness-like. How… weak?

“That is not a source of weakness,” Dworkis said on his Emergency Mind podcast. “That's not 'we're not capable of burning for eight hours.' That's 'we're trying to do the best possible.' We're trying to be elite performers. And elite performers balance action and recovery, across every field that I've had a chance to study. And every field that I've even remotely connected to. You balance performance and recovery.”

If you consider your work important, shouldn’t you work as if it is? And doesn’t that mean rest, recovery, and balance?

If that’s not enough, the more you work the worse your work gets.

In David Dylan Thomas’ Design for Cognitive Bias, he mentions the study “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions,” which found that “the percentage of favorable rulings drops gradually from ~65% to nearly zero within each decision session and returns abruptly to ~65% after a break.”

If the implication isn’t clear, they’re saying that judges get harsher the longer they go without a break. That seems… bad. And it also seems like the same cause could have some effect on my judgement. Luckily no one asks me life or death questions.

But taking breaks and recovering requires some sort of…

Joyful Structure:

Leah and I have expounded on this topic before: “Structured Joy emphasizes the importance of maintaining enthusiasm by actively encouraging enjoyment while Joyful Structure stresses the importance of planning and environment in creating a path of growth and success.”

Astronauts like Chris Hadfield, as he writes in An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, know that “Success is feeling good about the work you do throughout the long, unheralded journey that may or may not wind up at the launch pad. You can't view training solely as a stepping stone to something loftier. It's got to be an end in itself.” How? “The secret is to try to enjoy it.”

Most of the time, astronauts are not in space. Some never get there. So how do they keep up with their training, their tasks, and the rest of their life knowing that none of it may pan out the way they hope? They enjoy the whole ride, which happens every day, and not just the ultimate liftoff.

Fishbach again, in Get It Done: “If you want to predict how much a person—including yourself—will stick to a resolution, ask how excited they are to engage in it rather than how important the resolution seems to be.”

If you don’t want to go to the gym, you won’t. If you don’t want to write social media content, you won’t. The answer isn’t to avoid exercise or marketing—it’s to find exercise and marketing you’ll actually like doing and will actually do.

Milkman again, in How to Change: “Anyone who has taken care of children knows it's absurd to tell them to focus on the long-term benefits of completing a chore. If it isn't fun, kids simply won't do it. Although adults have somewhat better neural circuitry for delaying gratification than children, we’re fundamentally wired the same way. We just fail to recognize it.”

We can pretend we’re big, tough grownups all we want. But we still fail like children because we act like them right up until the failure. By not planning. By not thinking things through. And by not making sure we actually enjoy the thing we’re supposed to do.

Ingrid Fetell Lee quotes Stuart Brown in Joyful: “The opposite of play is not work. It’s depression.”

Insisting that work be difficult or boring to be genuine is the same as insisting that we must be sad and depressed to be productive. Maybe for you, but certainly not for me.

In fact, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi wrote in Flow, “The key element of an optimal experience is that it is an end in itself. Even if initially undertaken for other reasons, the activity that consumes us becomes intrinsically rewarding.”

I want my career to be an optimal experience in my life. It seems worth making a few incremental adjustments to get there.

Incremental Adjustments:

Again, you’re not lazy for not being able will yourself into doing things you hate for a long time.

As Hardy says in Willpower Doesn’t Work, “Your willpower is gone. It was gone the moment you woke up and got sucked back into your smartphone. It was gone when you were bombarded by a thousand options and choices. White-knuckling your way to change doesn’t work. It never did. Instead, you need to create and control your environment.” Summing it up, perfectly: “Stop the willpower madness already.”

You are not the problem. You are not the problem. You are not the problem. The problem is your environment, and your only responsibility is to exert whatever control you have into adjusting your environment for the better, slowly and sustainably.

Putting too many things on us at once won’t work.

Milkman writes in How to Change, “Having too many plans can overwhelm us. If we form multiple cue-based plans for competing goals (to exercise more and to learn a foreign language and to get a promotion and to renovate the kitchen), we're forced to face the fact that doing everything required to succeed will be really tough. And this leads our commitment to dwindle, making it harder to achieve even one of our goals.”

Having lots of goals and ambitions is demotivating, not inspiring. Edit your goals to improve your effectiveness. Increments, not monuments.

So if it’s all about environment, what does that mean? One implication is that my attitude is related to my environment. My motivation is related to my workspace.

“Space is the body language of a company,” as Brendan Boyle said on the IDEO podcast.

Other people’s body language has a massive effect on me and my emotions and bearing in a situation. What is the body language of my office, and how am I responding to it?

To increase joy in my work, I can increase joy in my workspace.

Lee writes in Joyful, “Harmony offers visible evidence that someone cares enough about a place to invest energy in it. Disorder has the opposite effect. Disorderly environments have been linked to feelings of powerlessness, fear, anxiety, and depression, and they exert a subtle, negative influence on people's behavior.”

“Messy desk, messy mind” isn’t necessarily true or fair. But “overwhelmed office, overwhelmed occupant” might be something.

So when should I start making changes?

Fresh Starts and Change Moments:

I first heard the term “Fresh Start” from Katy Milkman on a podcast interview. In How to Change she emphasized that these moments, like the starting of a new year or after ending a relationship provide us with momentary motivation. This also means that “A particularly effective time to encourage other people— employees, friends, or family members—to pursue positive change is after fresh starts.”

A partial implication is that the New Year isn’t necessarily your time to make change, it’s just the time you’re most being marketed to about change.

Which reminds me of the Charlie Munger story. Frustrated that fundamental investing principles aren’t obvious to everyone else, and that so many people fall for silly schemes, Munger said, “I think the reason why we got into such idiocy in investment management is best illustrated by a story that I tell about the guy who sold fishing tackle. I asked him, ‘My God, they’re purple and green. Do fish really take these lures?’ And he said, ‘Mister, I don’t sell to fish.’

New Years Resolutions don’t work, but productivity courses marketed around New Years do sell.

Instead of assuming that a Fresh Start is the right moment to take massive action, maybe it’s the time to slow down and think?

“What if the biggest thing keeping us from doing what matters is the false assumption that it has to take tremendous effort?” McKeown wrote in Effortless. “What if, instead, we considered the possibility that the reason something feels hard is that we haven't yet found the easier way to do it?”

The answer to massive ambition isn’t monumental action. It’s tiny changes, and mostly to our environment.

“So how do you motivate yourself? The short answer is by changing your circumstances,” Fishbach wrote in Get It Done. “You modify our own behavior by modifying the situation in which it occurs.”

Seize Fresh Start moments to make tiny changes to your environment so that you want to do the things that will get you what you want. Instead of burning up all your enthusiasm in a compulsive lunge toward a “should” in your life.

As Richard P. Rumelt wrote in Good Strategy/Bad Strategy, “By definition, winging it is not a strategy.”

Announcing you’re going to launch a podcast or suddenly start posting every day on LinkedIn is like saying you’re suddenly going to go to the moon.

Without a plan and the resources to sustain it, you’re not going anywhere—because winging it is not a strategy.