“Make Me Laugh”: How to build a brand based on values

Darwin said that he “followed a golden rule, namely, that whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once.”

“History is the best help, being a record of how things usually go wrong.”

— Why Don’t We Learn from History?

There’s nothing I relish quite like a contradiction. I’ve always liked this idea from Charles Darwin, by way of Charlie Munger:

Darwin said that he “followed a golden rule, namely, that whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once.”

Whenever he encountered something that contradicted what he believed to be true about the world, he’d immediately write it down. Otherwise, he knew he’d forget about it and move on, and he’d remain ignorant of a potential new truth.

“Owing to this habit,” Darwin said, “very few objections were raised against my views which I had not at least noticed and attempted to answer.”

So whenever I come across something that contradicts my worldview or perspective, I write it down in the Golden Rule section of my notebook, and I attempt to either correct myself, find the error, or reconcile the new information.

So when I recently rewatched this 1997 video of Steve Jobs presenting the iconic Think Different campaign to Apple employees—well, reader, I had to write down another Golden Rule.

In this video, Steve Jobs makes a clear and forceful pitch for branding. For infusing the company with a feeling through its advertising.

Okay, no big deal, right? That’s what marketers try to do all the time.

But Steve wasn’t just some marketer. He’s the guy who hated branding!

"In Steve's mind," said former Apple VP of Worldwide Marketing Communication Allison Johnson, "people associated brands with television advertising and commercials and artificial things. The most important thing was people's relationship to the product. So any time we said 'brand' it was a dirty word."

Steve Jobs, the guy who hated branding, standing there, praising branding.

So I copied the link to the video into my notebook, and there it sat for me to dwell on.

Reader, this newsletter is the outcome of writing that single line into my notebook, and this represents—to the best of my ability—my complete perspective on branding.

Last week, after I’d marshalled my arguments and research, I put out a question to you all—what do you want to know about branding?

And multiple readers sent in a variety of questions all on the same theme: “How do I build a brand based on my values?”

The good news is, this is an easy question to answer. The bad news is, once I’ve answered it, you’re going to have a lot more questions.

So settle in, grab a beverage, and let’s get into it.

Part 1: Who Values Brand Values?

But first! Definitions:

Brand: A hot piece of iron used to mark ownership on livestock / The name or mark a company stands behind and uses to promote their product or service

Branding: Applying a hot iron to flesh / A marketing industry term for activities that highlight the values, perspective, traits, or qualities of the owner, the staff, and the customers who choose to stand behind the mark of ownership

Ghoulish, I know.

Put simply, “branding” is just the answer to the customer’s first, most obvious question: “Why should I care who made this?” Or, perhaps more crassly and accurately, “Why does this one with the fancy logo cost more?”

And it turns out there are two basic ways to build a brand based on your values:

Option 1:

Spend lots and lots of money advertising your brand values, creating enough of a sense of good feeling about your company that some amount of people will buy your product. Other people will see those people buying, encouraging them to buy for themselves.

As long as you continually grow your advertising spend, you'll be able to keep growing your business.

This strategy typically requires a great deal of upfront and sustained capital, and is usually chosen by commodities (because differentiated products have a cheaper, more effective alternative—see below).

But this path works for commodities because, if you can establish your brand in the mind of your customers, you’ll have an edge on competitors and copycats. As Al Ries and Jack Trout wrote in The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing, “Marketing is often a battle for legitimacy. The first brand that captures the concept is often able to portray its competitors as illegitimate pretenders.”

One way to “capture a concept” is by spending your way into the minds and wallets of your customers by reinforcing brand values in your advertising.

Option 2:

You can slowly but surely build a reputation the same way people have been doing it for themselves, since forever: You make promises, and then you keep them. Which is the essence of positioning.

Instead of just talking about your values, you demonstrate to your ideal customers the specific decisions and tradeoffs those values have caused you to make.

And, because your ideal customers share your values, they'll agree with those tradeoffs—meaning you'll be able to do less of what they don't care about (and don't want to pay for), and more of what they do care about (and would pay anything for).

Making these tradeoffs means you can promise your customers that they'll get exceptional value for their dollar (even if you’re a more expensive option), and they’ll agree once they’ve experienced your brand in their lives.

While this strategy requires little upfront capital, it does require patience. And it only works if you are not a commodity. It only works if there are real and meaningful differences in how you make or deliver what it is you sell.

That’s because, as Michael E. Porter wrote in Competitive Strategy, "Where the product or service is perceived as a commodity or near commodity, choice by the buyer is largely based on price and service, and pressures for intense price and service competition result.”

And that’s really that.

So to answer the original question, to build a brand based on your values you:

- Define an audience group you’re uniquely able to serve based on your overlapping values

- Make decisions and tradeoffs in your business to best serve those ideal customers

- Demonstrate how those decisions and tradeoffs have influenced your product or service offering

- Promote the additional value (in terms of cost savings, satisfaction, aesthetic appeal, etc.) these specific tradeoffs create for your ideal customers

But I can sense some hesitance.

Maybe a little resistance.

Because you weren’t asking me what to do in your business.

You were asking me what to say about your business, about your values, to get people to buy from you (or be willing to pay more for what you sell).

The problem is, no one actually cares about the values you talk about.

They care about the decisions you make in your business to demonstrate those values.

Here's how I can prove it to you: If I said my values were based in environmental stewardship and financial sustainability but I relished burning my trash and taking on massive debt, once you found out, you'd no longer care about my expressed values.

Because the only thing that actually matters is our revealed values based on the decisions we make and the actions we take.

So, what do your decisions reveal about your values?

That's what you talk about in your marketing. That’s what you build your brand around.

Of course, some might argue otherwise.

As Wieden+Kennedy CEO Neal Arthur put it on Decoder, for an big ad agency like theirs, it’s not about making sales for their clients directly. Instead, it’s about creating “emotional relationships to the brand that will then make them more open to buying products.”

And I suspect that when people ask me about branding, that’s what they’re really asking about.

They’re asking how they can make advertising that will get people to feel good about their company—so good that they’ll want to buy more of it, or even pay more for it.

Which isn’t necessarily wrong. And for massive businesses who’ve hit market saturation or commodities who have no differentiating features, it’s often the only option. But it is indirect.

And, as I’m about to argue, for businesses with true differences, it’s incredibly inefficient.

But first, we need to look at the bigger picture. Why do brands matter at all? Why does it matter what feelings people have about a logo?

Part 2: The Penalty of Branding

“Before the 1880s,” Juliann Sivulka notes in Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising, “the names of most manufacturers had been virtually unknown to the people who bought their products.”

But by the end of the century, modern manufacturing techniques, national magazines and newspapers, trains, and telegraphs allowed for a massive increase in local producers selling and advertising their wares further afield. The awareness of, good feelings around, and trust in a brand name thus became a major factor in sales outside of their home region, as well as within it.

Innovations in packaging—which not only allowed manufacturers to make their products more appealing, but also gave them more real estate to show off their brand—helped popularize brands on store shelves throughout the world, according to Sivulka.

So it made a lot of sense for businesses to want to use the new advent of mass media (in the form of national newspapers and magazines) to increase trust in their brands. And, in the early days, the very fact that you could afford to pay for advertising was enough to demonstrate that you were a credible company.

Because, as business strategy legend Hamilton Helmer points out in 7 Powers, having a powerful brand is valuable for two key reasons:

“Affective Valence: The built-up associations with the brand elicit good feelings about the offering, distinct from the objective value of the good.”

(You can charge/sell more because people like you)

“Uncertainty Reduction: A customer attains ‘peace of mind’ knowing that the branded product will be as just as expected.”

(You can charge/sell more because people trust you)

But it's not a direct line from wanting your brand to be known for something and having it be so.

Nor is it a direct line from promoting your brand values to making sales.

That doesn’t mean people haven’t tried—or aren’t still trying. This style of branding, originally called “atmosphere advertising,” kicked off in the 1910s.

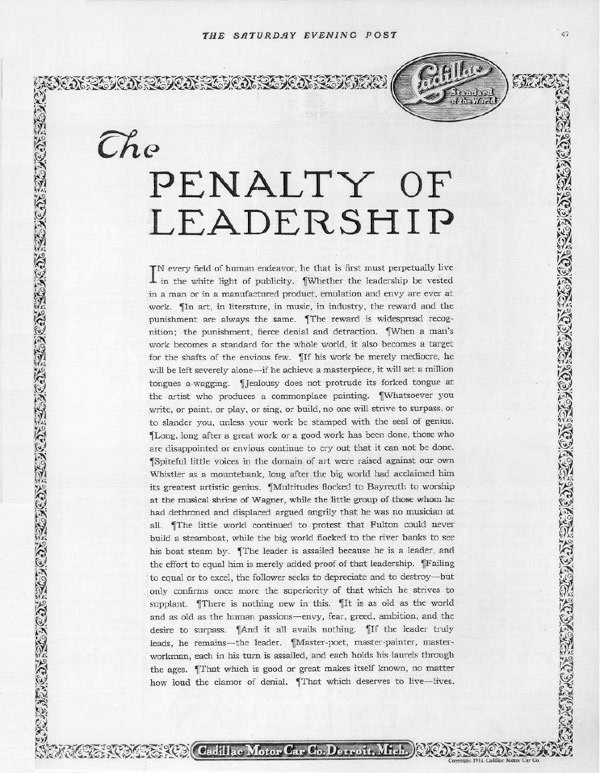

Theodore MacManus, pushing back against the prevailing “hard sell” advertising of the late 1800s and early 1900s wrote this famous 1915 Cadillac ad. It represents the style reaching an early peak:

In fact, thirty years after the ad first appeared—and it only ever ran once—readers of industry magazine Printers’ Ink voted it “The greatest advertisement of all time.”

You'll notice that the ad doesn't mention the product, or even have a picture of one. It's just lines and lines of text about how tough it is to be the best.

It’s all values, all feelings—all brand.

Cadillac's still around today (and doing plenty of emotions-based brand advertising), so it worked, right? Well, sort of, but we’ll get back there.

But I didn’t say, nor do I think, that promoting brand values can’t create sales or even build brand recognition (allowing you to slowly back into making sales).

What I’m saying is that it’s extremely expensive, costs more and more every year, and there’s another, more sustainable option.

Throughout the last 150 years, the prevailing style of advertising has bounced between harder selling and lighter, more atmospheric branding. But as Stephen Fox pointed out in his advertising history The Mirror Makers, it's usually the case that “hard times meant a hard sell.”

That is, once people started getting more careful about where they were spending money, merely promoting brand values and hoping for sales became less and less popular—because it just doesn’t work as well.

In the 1950s, for instance, as the world reassembled itself post-WWII, Rosser Reeves’ style of hard-driving, Unique Selling Proposition-focused advertising became fashionable: the hard sell had met its hard time.

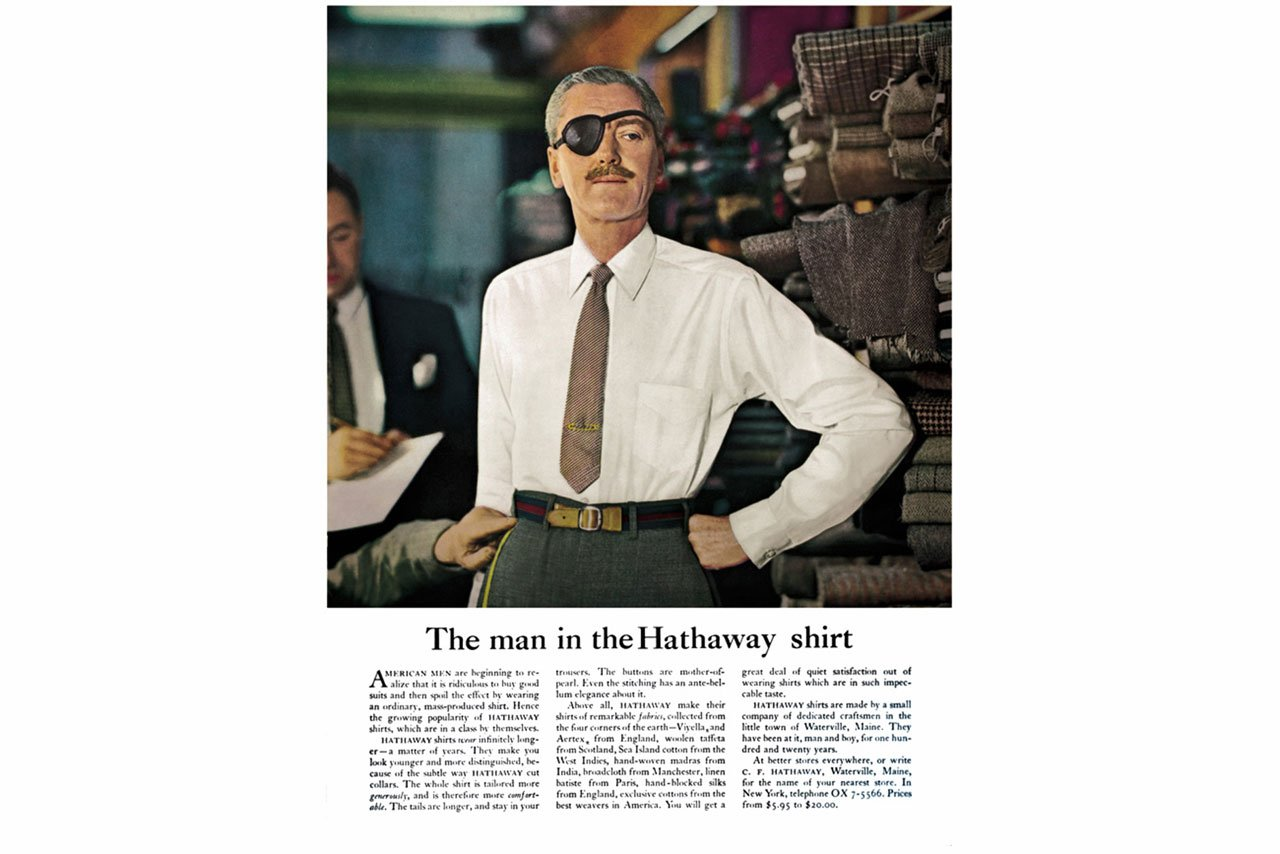

That lasted for a little while, and advertising agency icons like David Ogvily built their names by combining creative, eye-catching ads (what he called “story appeal”), with facts grounded in reasons why the customer should purchase.

People don’t buy a product because the ad is funny, he’d insist, they bought because it promised a benefit—the fact that it was funny was what got them to pay attention at all.

Or as “The Socrates of San Francisco,” Howard Gossage, put it, “People don’t read ads. They read what interests them. Sometimes it’s an ad.”

Ogilvy himself was inspired by the earlier hard-sell era presided over by folks like Albert Lasker (“The Man Who Sold America”), John E. Kennedy (who famously defined advertising as “salesmanship in print”), and Claude C. Hopkins (about whose book, Scientific Advertising, Ogilvy said no one should have any place in advertising until they had read it seven times).

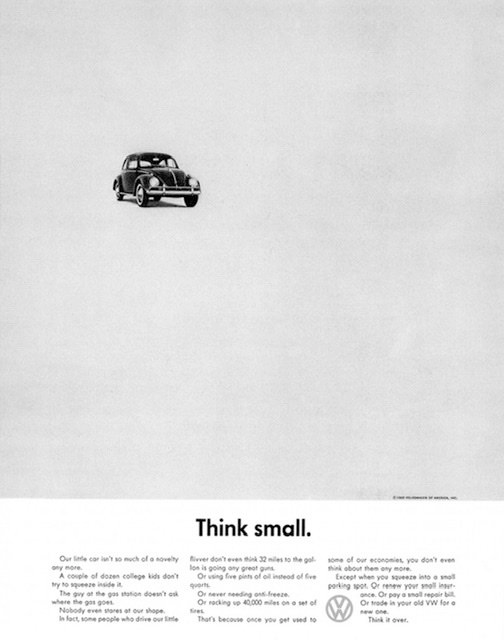

But as the economic times recovered, the post-war boom of the 1960s coincided with the “creative revolution,” led by Mad Men-era icons like Bill Bernbach at DDB.

According to Dominik Imseng in Think Small, his history of the classic VW campaign, Bernbach argued that Reeves’ “Unique Selling Proposition” was only the starting point. Ogilvy’s “research” was a crutch.

The real magic was in how the information was communicated. “If breaking every rule in the world is going to achieve that,” Bernbach said, “I want those rules broken.”

Mary Wells Lawrence, who worked closely with Bernbach at DDB, wrote that he’d said of proponents of the harder-sell school of “Scientific Advertising”:

“Either they were liars or they were stupid; their pitiful research reduced advertising to, basically, one poor tired ad that was repeated over and over again.”

So, the selling got softer. But, once the economy faltered again, so did the sales.

In fact, from 1971–1973, DDB lost $59 million in billings from departing clients, according to Fox.

It turned out that, as Reeves had rightly predicted years before, “During the 1970s … Big business will return to the immutable advertising law that the agency must make the product interesting, and not just the advertisement itself.”

This pullback from traditional branding and creative firms coincided with Jack Trout and Al Ries pulling themselves out of advertising obscurity by popularizing the concept of “positioning.”

This inspired a renewed shift toward clearer ads focused on real, promised benefits (rather than just cleverness, positive feelings, or creativity for its own sake). Ogilvy himself believed this was a return to the harder-sell form that he’d helped popularize in the previous decade.

Trout and Ries, writes Fox, were so bold (and so wrong) as to say that the rise of positioning meant that “today, creativity is dead.”

But, as tides tend to do, it turned.

As the economy and spirits lifted during the 80s, famous ad creatives like Lee Clow and Hal Riney made their names—primarily by pushing against hard sales pitches and leaning toward what Riney called “communicating through suggestion.”

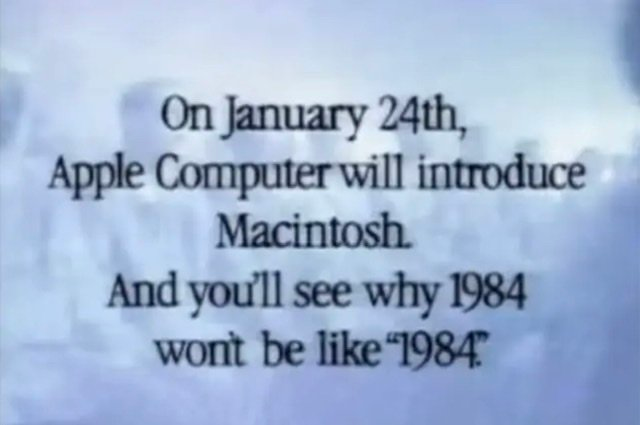

This era is marked by Clow’s 1984 ad for Apple, which extravagantly counter-positioned a vibrant, youthful Apple against the old, stodgy suits at IBM.

Just as things were getting going, though, the recession of 1987 caused a cutback in advertising spending that lasted until the early 90s. Sivulka writes that this led to businesses shifting ad dollars to “more cost-effective promotion alternatives, such as coupons, direct mail, and direct marketing.”

In 1992, she writes, “sales promotions accounted for 73 percent of the ad promotion budget, compared to 28 percent for advertising.”

But by the end of the decade, with a booming economy and rising consumer confidence, branding ads took priority again. My childhood memories, I’ll admit, are infused with the provocative branding ads for traditional commodities like blue jeans (Levi’s), fragrances (Calvin Klein), and soft drinks (Pepsi).

While the dot-com bust, the stock market decline, and 9/11 shook culture and the economy—leading to a record decline in advertising spending—Sivulka notes that consumer and advertiser spending recovered quickly, and the post-9/11 period of the mid-2000s saw the rise of “branded entertainment,” a pre-cursor to the rapid ascent of “content marketing” in the 2010s.

Ad industry followers might remember this time for the ascent of creative agency Crispin Porter + Bogusky and their headline-grabbing work for challenger brands like Burger King (including the bizarre but attention-getting “Subservient Chicken” campaign).

And, then, of course, disaster.

The advertising industry was seized with rounds and rounds of layoffs during the 2008/9 economic crisis and recession as businesses pulled back on brand spending, yet again.

Billions of ad dollars pivoted to newfangled pay-per-click search, social media ads, and digital display. Coincidentally, alongside a global economic collapse, Apple initiated a tectonic economic shift with the launch of the App Store for their brand new iPhone, in 2008.

Suddenly, the mobile web began transforming media, as everyone started spending more time with the computer in their pocket than with their TV, their desktop, or their friends.

Facebook went all-in on mobile in 2012 and digital advertising, fuelled by deterministic data about who’s purchasing what—based on specific ads, at what times, and in which places—took even greater precedence over traditional branding.

Luckily for fans of pure value-based branding, the pivot to hard selling, direct marketing wasn’t permanent or fully pervasive. Because then began the gold rush of digital-enabled commodities, like generic mobile games, food delivery apps, car sharing services, meal kit companies, health apps, and box-of-the-month-clubs.

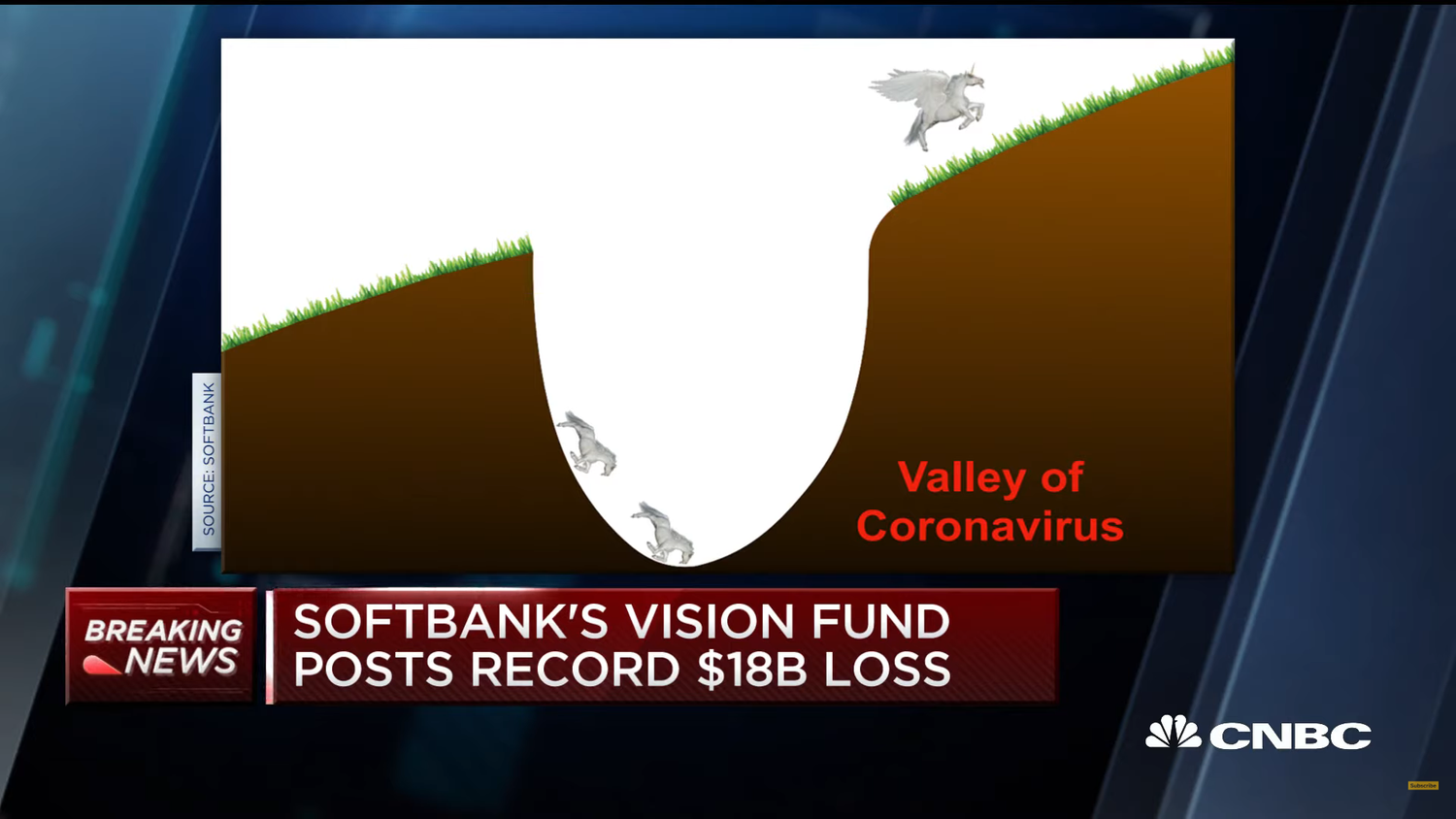

Venture capital poured into startups, and SoftBanks’s Vision Fund dumped the world’s biggest pile of its very dumbest dollars into undifferentiated startup after undifferentiated startup.

By the late-2010s and early 2020s, tech companies, desperate to separate themselves from an ever-growing set of identical competitors, returned to the advertising pioneered by their late 1990s boom-time forbearers: running generic and vague ads during the “Big Game” (which usually don’t work) and buying naming rights to stadiums.

Unfortunately, trying to spend your way to profit rarely goes great, for all the obvious reasons. Because diminishing returns. Because competition. Because regulation. Because events.

Because, you know, reality.

And the reality is, it’s not one or the other. It’s not brand advertising or product positioning.

The answer is, always has been, and always will be both.

The history of advertising tells us clearly, plainly, and resoundingly that the way to build a brand is to sell products. And the way to sell products is to make and keep promises that matter to your customers.

And to be able to make and keep promises that matter, you need to make decisions and tradeoffs that uniquely benefit your best customers.

And your ads need to show what those decisions and tradeoffs are.

Because when you don’t talk about your product and when you only talk about your brand values, well, you’re advertising something else entirely.

You’re advertising to your customers and to the world that you can’t promote your product.

Part 3: All Brand, No Value

Let’s take a look at Bubly to show you what I mean. Perhaps for my readers in the U.S. their approach is different, but up here in Canada, Bubly ads can be pretty hard to escape.

The brand is PepsiCo’s attempt to preserve market share as consumers switch to unsweetened soft drinks. It has no moat—no unique feature, process, cornered resource, or position. But what they have is money, and they’re spending that money on branding (via a famous spokesperson).

There’s obviously nothing wrong with Bubly as a product—I drink it, I like it.

But because there’s no real reason to buy it over an alternative—nothing unique or interesting about the product itself—other than that it’s the one you’ve heard of, they have to spend millions of dollars to make sure you’ve heard of it.

Because no one else is going to tell you about it.

And, so far, so goo- well, they somehow lost market share last year despite all those ads. So I guess we’ll see.

Worse, though, they can never stop or slow their advertising. Because their strategy relies solely on making sure people keep hearing about them, if they ever stop, people will forget about them.

Even worse than that, they can’t just not stop, they have to spend more and more.

Due to those pesky diminishing returns, every time Bubly spends a dollar on advertising, it has a smaller effect than the dollar before it. Every additional dollar is reaching people who have less and less awareness and less and less interest in the product (or in Michael Buble). So to keep getting people to notice them, PepsiCo has to spend more and more—forever.

Because pure brand advertising, unlike product positioning, doesn’t compound with time—it diminishes.

As best selling author and advertiser Ryan Holiday wrote in Perennial Seller, “Anything that requires advertising to survive will—on a long enough timeline—cease to be economically feasible” because of diminishing returns.

Word of mouth, however, compounds.

People who like your product because it’s uniquely valuable to them (based on the decisions and tradeoffs you’ve made) tell other people about it (because they know their friends will appreciate those same tradeoffs).

Those people tell other people. Those people tell other people. And so on.

Word of mouth is so important for a brand to sustain itself because we simpy trust our friends more than we trust ads. Even more than we trust Michael Buble, God bless him.

That’s why, as Holiday says, “a product that doesn't have word of mouth will eventually cease to exist as far as the general public is concerned." But a product with word of mouth can spend so much less, and make so much more, because their customers are doing their advertising for them.

You can always spot when a brand is trying to skip to the end of the product adoption curve. They want to get right to the place where they’re a household name and people buy them out of habit, so they pay a famous celebrity to appear in their early ads.

This is an attempt to splash some of the celebrity’s goodwill and fame onto the brand and create the perception that the brand is famous and important, just like the celebrity.

But building a brand based on the reflected fame of celebrities, influencers, or spokespeople is like trying to breathe by sucking in someone else’s expelled air. It’s better than nothing and it’ll do in a pinch, but you won’t want to keep it up for long. And if the spokesperson ever does anything publicly wrong, they’ve now poisoned the air you rely on to survive.

Nothing like a bargain with a limited upside and an unlimited downside.

It turns out, Apple was here in 1997.

Because, that’s the thing that I realized about the Think Different ad I mentioned at the very top of this story (so, so long ago).

1997 was the year Steve Jobs returned to Apple after his infamous ouster. An Apple that was months away from bankruptcy.

An Apple that had been run into the ground through bad partnerships, generic products, and a complete lack of position.

So Steve came back and launched a brand campaign to drum up support for Apple. Why? Because, at that moment, they had nothing else.

Think Different was resuscitation, a lung-full of air pumped into the brand via Richard Dreyfuss and a collage of people far more famous than Apple. The recycled and reflected fame of others.

Why? To create a mood, a vibe, a positive feeling about the company.

To promote their brand values.

So that their core customers would buy a bit more. Stick with them a bit longer. Have something to feel good about until the products got better.

Which they did, the very next year, with the launch of the first colourful iMacs.

Steve knew what no one else did—that the branding campaign was temporary, a stop-gap, not a solution. Until they had something far, far better than branding:

A position. A reason to exist and a reason to buy, overlapping in consumers’ minds and motivating them to spend.

I mean, take a look at these original iMac ads:

Just like Rosser Reeves insisted (“The best theoretical objective is to surround the claim with the feeling.”) they surround the selling proposition (the iMac is so much easier and friendlier to use than your ugly, cumbersome PC) with a feeling (the charming tone and casually comfortable style of Jeff Goldblum).

They’re not using Goldblum’s fame to push the product, or his name to borrow clout—they’re using his talents to promote their product. Creatively, convincingly. Effectively.

Once you buy and experience the product, you’ll fall in love with the brand.

And you’ll buy more and you tell your friends to buy, too—because you know they’ll appreciate the decisions and tradeoffs that Apple made when designing the product.

Oh, and that 1915 Cadillac ad from earlier, one of the most famous early branding ads? MacManus came up with the concept for that one because their competitors were making a mockery of Cadillac’s new vehicle, which, as Stephen Fox notes in The Mirror Makers, was quickly becoming most known for its defective engine.

Cadillacs were also several times the price of the more reliable Fords of the day. So what did they do? They retreated to branding to gain them some time to improve their cars, and their reputation.

Which means, at its worst, branding without any product positioning is an admission of commoditization, or defect.

It spreads feelings of goodwill, but it also communicates that the product has no unique purpose. And that the company is willing to buy every sale at a hefty price.

At its best, it reminds existing customers why they buy, and they spread awareness and familiarity of the logo and the brand’s name.

It gives people enough good feelings that some of them will end up buying, as long as they keep seeing the ads.

And at their typical most, they take credit for sales that were going to happen anyway.

Sales that would have happened just by throwing up a billboard that says, “Hey, we sell that thing you want” (as some brands are famous enough to get away with).

So if your product or business actually does something, anything, focus your advertising on that.

Build your reputation by consistently marketing and selling your product based on what makes it unique and different.

And wrap that position in the style, feeling, and, yes, the values of your brand.

But don’t simply shout your values, reveal them.

Live them.

Demonstrate the business decisions you're making to reinforce them.

If you try to skip to the end—right to just reinforcing brand values—even if you can spend enough to get the best celebrity, produce the funniest ad, and buy enough media space to make a splash, you’ll never be able to stop. Ever.

And then, when budgets get cut or spending pulls back, well, as Warren Buffet famously says, “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

Part 4: The Other, Better Way

So if you want to market efficiently enough to keep it up for the long-term, you’ve got to reinforce a unique position.

You need to stick in the mind of the customer, into a category that’s valuable to them—one that fits a “Job to Be Done” and which will occur to them when they reach their “struggling moment.”

But to reinforce a position, you’ve got to have one.

And then you’ll need just as much creativity as branding ads require, but focused on what matters—what the customer values, and how the company’s values reinforce their own, as demonstrated by the way the product or service is designed, made, or delivered.

As Mary Wells Lawrence wrote in her autobiography, when you’re making an advertisement, “There is nothing better than a fact if you have a great one.”

But that’s not enough. The ad has to be creative and catchy enough so that it would “stay fixed, enticingly, in your mind, it wouldn’t let go of you.“

According to Lawrence, “That’s what branding is supposed to do.”

Apple’s famous “I’m a Mac and I’m a PC” ads were clear product positioning ads, focused on the decisions Apple had made to differentiate their products from their competition. But they wrapped it in their brand style and perspective.

Because it’s not just that Steve hated empty branding.

As Allison Johnson, the former Apple marketing VP I quoted above said, what was most important was that “the marketing team was right next to the product development and engineering teams. So we understood deeply what was important about the product, what the team’s motivations were in the product, what they hoped that product would achieve, what role they wanted it to have in people’s lives.”

Product and marketing, together, where they belong.

“And because we were that close,” Johnson says, “we were able to translate that very clearly in all of our marketing and communications.”

The best way to build a brand based on your values, then, isn’t to try.

It’s to sell your products or services to the people that want them most, and then to get your customers and prospects to notice that your business aligns with their values.

That’s how you build a brand. That's how you build your reputation.

Some of my favourite examples include the original ad by Dollar Shave Club on the smaller and scrappier end, and this explainer video by the greats over at Sandwich for the podcast editing app Descript:

It’s not enough to be creative. It’s not enough to be positioned. It’s both, always.

These examples are coated in branding, but that coating surrounds a position—a claim, a benefit, a promise.

Expressed values that the positioning reveals.

I know, I know, but what about Nike? What about Coca-Cola? What about the famous companies who are all brand, all the time? Don’t they prove that all you need is a great brand, a great logo, and some great ads that make people feel good?

Well, it’s true, Nike has built a great deal of their fame and fortune on branding and celebrity endorsements.

But that’s not how they started. We need to ask ourselves how Nike and Coca-Cola made so much money that they could go on to spend it on branding ads.

Nike didn’t actually run their first “brand” ad until 14 years after the company was founded (originally as Blue Ribbon Sports), at which point their annual revenue was approaching $100,000,000. And their first product was, of course, brand new to the U.S. market—the Onitsuka Tigers they were importing from Japan—and therefore differentiated by default.

But as the running shoe and sports apparel industries exploded during the 70s, Nike started more aggressively branding, to give customers more reasons to buy from them as their product became increasingly commoditized by competitors. In fact, between 1971 and 1981, “there was an 1,800 percent increase in marathon finishers, and … running shoes became more popular.”

Yes, Nike spends aggressively on branding, and they have to spend more and more [] every year, but even with them it’s not one or the other. Because it’s also impossible to ignore the number of innovative and exciting new products Nike launched over the decades, including the Air Max and the Zoom Fly.

(Also, I can’t possibly write about Nike’s branding without letting you know that “Just do it.” was inspired by the last words of a death row inmate (“Let’s do it.”). So, yeah, there you go.)

For Coca-Cola’s origins we’ve got to go back to the patent medicine days of the 1800s—medicines that, famously, didn’t actually work.

“Scheme men” of the day, as early advertisers were called (yes, really), invented features and benefits for these patent medicines that they would then promote to unsuspecting and desperate customers. Eventually, though, advertising regulators forced them to start making claims that edged nearer and nearer to the actual truth—that these “medicines” did nothing, they just tasted good. So that’s what Coca-Cola’s brand is all about. Flavour, feeling.

Coca-Cola has never been a product that served a function, it’s always been about a feeling. That feeling was originally “maybe this weird tasting beverage will cure my illness.” Over time it became, “maybe indulging in this sweetly acidic drink will make me feel better than I do right now.”

They can do nothing but branding, because the product is nothing but a brand. And with only a few exceptions for global economic crises, Coca-Cola has also had to increase their marketing spend every single year, and they’ll never be able to stop.

So when we look at big brands making the fun, creative ads we admire, we need to ask ourselves not, “How can I build a brand like that?” but “How did they build a brand like that?”

And the answer is almost never by advertising brand values.

The answer is by selling products.

TAG Heuer didn’t get where they are today because they put celebrities in their branding ads. They can afford to put celebrities in their ads because the company invented and patented some of the most important components used in mechanical watches.

Your brand won’t get famous, wow customers, or gain the attention of important industry peers or partners by making a few clever ads.

It’ll get there by selling a lot of great products or services, to the people that value them most—and those people will make your brand famous.

To sum it all up:

The best way to sell your products and services is by first creating a compelling position that differentiates you in the market.

You do that by focusing on the decisions and tradeoffs in your business that your values have caused you to make, and the customers who will most appreciate those tradeoffs (and the extra value it provides them).

And then you promote and reinforce that position by creatively wrapping it in your brand style and values.

And you target your very best customers where and when they experience their moment of greatest need.

So let’s say you sell a luxury product, like custom jewellery as one of my most beloved readers wrote in to ask about. This reader also wanted to know how to attract the attention of some high-end retailers.

So what do you talk about? Well, you talk about how your unique perspective, experiences, or values have led you to make decisions and tradeoffs that your best customers will appreciate and value.

So, what does luxury mean, in your ideal customers' terms, other than simply expensive? For instance, if I were your target customer, you'd want to focus on attention to detail, as that's my personal synonym for luxury.

That's why, for me, luxuries are often expensive (it's costly for the manufacturer or service provider to pay attention to the details), but why I don't consider all expensive things luxuries (just because I'm paying them to pay attention to the details, that doesn't mean they are, or that they pay attention to the details I care about).

So I'd want you to demonstrate to me the details you pay attention to, and hopefully they're the same ones I care about. Because if they are, then I'm likely to buy.

But simply telling me that your jewellery is special or that you have interesting values—or even that you pay attention to detail—that doesn't mean I'll like the thing you're trying to sell me.

But if you demonstrate to me the specific ways in which that attention to those details add value to my experience, then I'll know our priorities overlap. And I’ll know that you’re the right person to work with on my custom jewellery.

Not just because you say the right things, but because you demonstrate doing the right things.

So the question I’d ask is:

In everything you do, from your website, to your social media, to your invoices, to your one-on-one customer interactions, to your Zoom backdrop, to your email signature—are you demonstrating that your unique abilities, interests, and experiences have led you to make decisions and tradeoffs that uniquely benefit your ideal customers?

Or, do any of those look like the rest of your industry? Does anything you do lead you to blend in with the rest of your competition or peers?

People already know where to go for jewellery. High-end stores already know where to find the best. What people need to know, what retailers will care about, is not what makes you great. Because, in your industry, great is the floor, it’s the least of their expectations.

What they want to know is what makes you meaningfully different.

So once you’ve aligned everything in your business to reinforce your position and your unique decisions and tradeoffs, then your ads can be about those tradeoffs.

You make your ads about the part of your process that’s unique to you. The way you work with your clients that you can do that no one else can. The specific techniques you employ, and why. The unique perspective you bring to the work and how it changes the end product, or the delivery of the experience to your clients.

Not your expressed values—your revealed values.

Another wonderful reader asked about how they can build a brand for their design business around environmental stewardship, over pure profit.

Well, dear reader, I'd turn that back to you: How are you demonstrating that?

Because, if your business ran identically to everyone else's in your category, by what measure would you be meaningfully focused on the environment?

So tell me what you're doing differently.

Some will assume that an environmental perspective will cost them more (even if that’s not always true) but they’ll know it's worth it if you tell them where that money's going.

Demonstrate what you're able to do that others cannot. How does your service meet my needs better than anyone else's, if we share this value?

Do you use or eschew certain materials, work styles, buildings, or locations? What are your office/work policies, and how do they demonstrate your zeal for the environment?

Putting a slogan on the side of your van that says, “I care about the planet” doesn’t make anyone want to buy from you any more.

But putting a sign on the side of your ebike that says, “I pass my fuel savings on to you”—well, that might.

Claims are great and can get you far for a while. But eventually somebody checks—eventually your customers actually experience the thing.

Your supposed brand values, in that moment, are either pleasantly reinforced or revealed to be empty.

And that will determine whether your company achieves the positive word of mouth it will need to develop into a brand people care about.

So don't tell me what you think or feel.

Show me what you do.

Because you don’t build a brand, you receive it based on what real people think about you—not what you say about yourself.

So don’t try to build a brand based on values.

Do the work to deserve one.

Your best customers will appreciate it, and they’ll make more customers for you.

But, it turns out that the “Ad Contrarian” Bob Hoffman already wrote everything that needs to be said on the subject in his book Marketers are from Mars, Consumers are from New Jersey:

“You want customers raving about your brand?” he writes.

“Sell them a good f-ing product.”

Or, maybe to close on something a little less aggressive, from Dave Trott:

“Don’t tell me you’re a comedian,” he wrote in One Plus One Equals Three.

“Make me laugh.”