What would an artist do? — Kelford Labs Weekly

Because *you* are one.

What would an artist do?

Do you ever ask yourself that question? Maybe it’s time you did.

Because marketing is partially a creative act. As a communicator, your everyday work is also, at least in part, creative. You’re not just rehashing best practices or copying the latest trends or popular advice.

You’re generating new, novel ideas and solutions to your clients’ unique problems. That is at least as much art as it is science. At least as much creative expression as it is consulting.

But are you treating yourself like you’re a human artist, or like you’re a programmable robot? Are you remembering to refill and refuel your creativity, or are you trying to brute force it?

Say you’re sitting down to write a LinkedIn post, or a newsletter, or to revise the copy on your homepage. Are you setting yourself up for an inspirational, motivational, and joyful process?

Or are you telling yourself to buckle down and churn it out?

You know I’m asking this because I already know the answers. You’re a professional, after all. You take your work seriously. And you’d never deign to diminish your professionalism by treating yourself like a mere artist.

Right?

Right...?

Well, today I’m here to gently bully you into remembering your work is part art and you are part artist.

The marketing you do for your business requires creativity, and you are creative. But you’ve got to treat yourself that way, at least a little bit and at least occasionally, to get the best results from your creativity.

Because that’s what this is all about: Not self-care for its own sake (though that is good and worthwhile!) but for your clients’ and prospects’ sake. Because for them to understand what you do and why they should work with you, they need to notice you.

And you’re never going to get their attention, their interest, or their buying intent without a little dose of creativity.

Good news: Art makes you inventive.

By treating yourself like an artist you’re not diluting your quality or your thinking ability, you’re improving it. It’s no coincidence that, according to David Epstein in Range that, “Compared to other scientists, Nobel laureates are at least twenty-two times more likely to partake as an amateur actor, dancer, magician, or other type of performer.”

Filling your mind and, if you’ll allow the metaphor, your soul, with artistic inspiration makes you better at your work. Why? Because that’s the nature of invention.

Steven Johnson wrote a whole book about where good ideas come from, titled, surprisingly enough, Where Good Ideas Come From, and in it he writes, “When we look back to the original innovation engine on earth, we find two essential properties. First, a capacity to make new connections with as many other elements as possible. And, second, a ‘randomizing’ environment that encourages collisions between all the elements in the system.”

And, sure, that applies to big ideas and inventions in the sciences, but does it apply to what you and I do? To things like consulting, coaching, marketing, and communicating?

I’m so glad you asked, because here’s what advertising legend David Ogilvy had to say about writing great advertising: “Stuff your conscious mind with information, then unhook your rational thought process.”

That sounds suspiciously like the advice Steven Johnson was giving, right?

In fact, Johnson writes, “The patterns are simple, but followed together, they make for a whole that is wiser than the sum of its parts. Go for a walk; cultivate hunches; write everything down, but keep your folders messy; embrace serendipity; make generative mistakes; take on multiple hobbies; frequent coffeehouses and other liquid networks; follow the links; let others build on your ideas; borrow, recycle, reinvent. Build a tangled bank.”

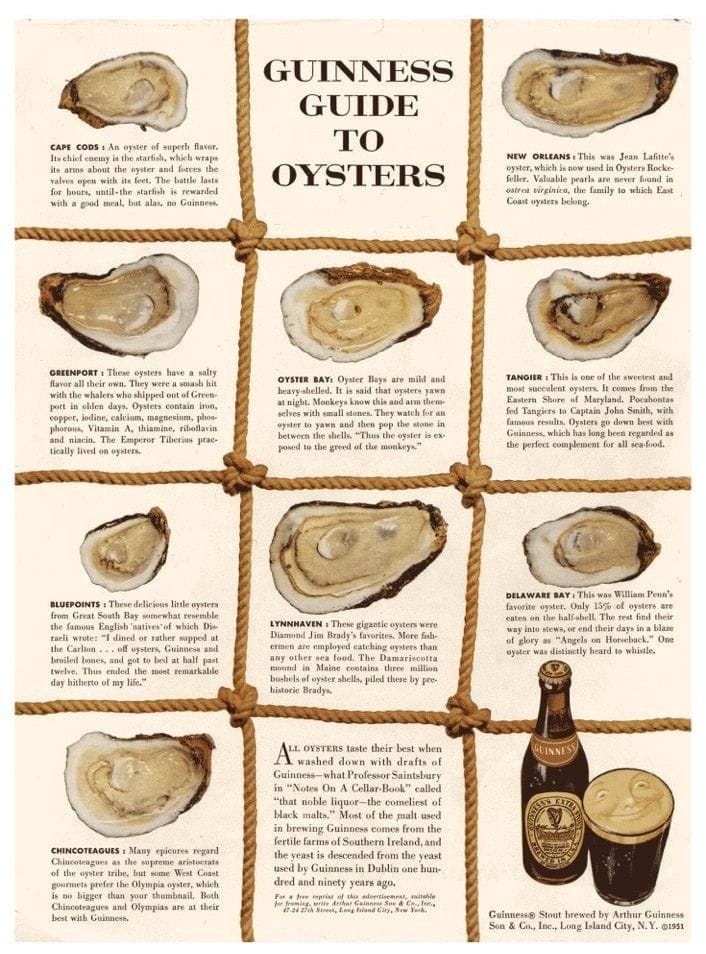

Ogilvy was pioneering what we’d now call “content marketing” back in the 1950s with his campaign for Guinness:

And you might imagine he sat studiously at his desk for hours, trying to brute force an idea that would catapult him to fame and fortune. But, no. He came up with the idea on the train, on the way home from work.

His biographer, Kenneth Roman, puts it this way in The King of Madison Avenue: “The idea was to borrow interest for Guinness from the fascinating foods you drink it with. Immersing himself in a Yale biologist's book on shellfish, Ogilvy conceived ‘The Guinness Guide to Oysters,’ a guide to nine varieties of oysters.”

Ogilvy had built a “tangled bank,” as Johnson put it, allowing his mind to act creatively even while he was doing other things.

But this isn’t just about being creative or interesting. It’s about getting results. So I’ve got more good news for you:

Art makes you effective.

I mean, Ogilvy knew this, too. He wrote: “When I write an advertisement, I don't want you to tell me that you find it ‘creative.’ I want you to find it so interesting that you buy the product.”

That’s what we’re all aiming for, and art helps us do that, too. Bill Bernbach, Ogilvy’s contemporary and competitor, led the “Creative Revolution” in advertising in the mid-20th-century. But, for him, creativity wasn’t a nice-to-have or a stylish surface layer.

“Properly practiced,” he said, “creativity can make one ad do the work of ten.”

As consultants, as advisors, as marketers, as communicators, we’re playing a game of attention. And “you cannot bore people into buying your product. You can only interest them into buying it,” as Ogilvy noted.

So we’ve got to nurture the side of ourselves that thinks, writes, speaks, and advises creatively. Like Scott L. Montgomery wrote in The Chicago Guide to Communicating Science, “recognizing good writing for what it is can be the first step to actually doing it yourself.”

And recognition starts with immersion. With spending time with art that inspires, challenges, and excites us. That shows us the way to express our own ideas more creatively, and shows us the way to having more creative ideas in the first place.

Personally, I watch a lot of movies, and often the same ones, over and over and over again until I can see and study each element. Until it’s second nature to question, “Why did the director do that, right then?”

I try to read widely, and on my desk right now I’ve got a 1,000-page fantasy-adventure novel, an out-of-print textbook from the 70s on inferential semantics, a classic piece of literature from the 1800s, a proto-cyberpunk novel, a history of piracy in the 1600s, and a book about the evolution of American politics in the 1990s.

That’s just what I’m reading and studying right now, and all of it is mixing into and interacting with everything else I’ve read and understand.

Because we need creativity to have good choices for our marketing, and we need to fuel it to be able to make decisions that matter and make a difference. Otherwise, we’ll fall into default patterns, or end up copying what everyone else is doing.

To be effective in marketing, we need to be original. And what is that but being creative?

Like Jennifer Riel and Roger Martin wrote in Creating Great Choices, “The definition of integrative thinking has always contained within it the creative act: it is ‘the ability to face constructively the tension of opposing models and instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, to generate a creative resolution of the tension in the form of a new model that contains elements of the individual models but is superior to each.’”

Originality, though, is risky. It means sticking our necks out, standing out from the crowd, and demonstrating what makes us different.

Which takes a good amount of bravery. But I’ve got good news there, too:

Art makes you brave.

After all, as Bernbach said, “If you stand for something, you will always find some people for you and some against you. If you stand for nothing, you will find nobody against you, and nobody for you.”

There’s no way to do marketing that isn’t, in some small way, risky, brave, and bold. Otherwise we’re not really marketing, are we? We’re blending into the background noise of the market.

We’re painting ourselves in business camouflage.

“All creative thinking about the future starts with experiments,” says Margaret Heffernan in Uncharted. Which means “feeling our way through a changing landscape, finding boundaries and contours.” But that isn’t always easy, and it “requires resilience because the route itself is uneven.”

But if you let yourself think like an artist, you’ll find more of that bravery. Because artists must be brave. If it’s a rehash, a regurgitation, a remake of something someone has already done, it isn’t art. It’s barely even content.

And it certainly won’t work. It won’t get attention, change a mind, or create a prototype for others to imitate. It’ll just... blend in and fade away.

Which means we also need to think about automation tools, like AI, a little bit more like how an artist would. Because most of them understand that by handing over our thinking to an AI tool, we’re handing over more than a task.

We’re surrendering our voice.

“The automation paradox is a physical reality,” Heffernan writes. “The more we surrender to the authority of devices, the less independent and imaginative our minds become, just when we need them most.”

That’s hard, because the one thing we know for sure when we use AI for our content is that it’s... fine. It’s good enough, or at least seems that way.

Heck, it’s better than nothing, right?

Maybe not.

Remember, as Hugh Macleod put it in Ignore Everybody, “The more original your idea is, the less good advice other people will be able to give you.”

If ChatGPT is able to give you good advice about something, it’s almost by definition not novel. Yes, you can create a custom GPT like I did that provides my original advice and not its own, but how many people are doing that?

I get the impulse and the urge to hand over the creativity to a tool, but we’ve got to resist it. We’ve got to take pains to be original, to be creative, to be ourselves.

Remember, as best-selling author Ryan Holiday writes, “You don't have to be a genius to make genius—you just have to have small moments of brilliance and edit out the boring stuff.”

That’s the art of being an artist: Putting in the time, energy, and effort to be original. To be yourself.

That’s all genius is, anyway. The most influential advertising copywriter of all time, Claude C. Hopkins, said it the best way I’ve ever heard:

“Genius is the art of taking pains.”

Sometimes, that means taking the pains to treat yourself like an artist, to find inspiration in art, in hobbies, in things that are not your work.

So let yourself be inventive. Let yourself be effective. Let yourself be brave. By letting yourself be an artist. At least a little bit, at least sometimes.

Why not start today?

Take a break, read a book, watch a movie, listen to some favourite music, or just go for a stroll outside and try to notice things the way an artist might notice them.

Just do something to treat the side of yourself like the artist it is.

Like the artist you are.

So you can be the best communicator you can possibly be.

Reply to this email to tell me what you think, or ask any questions!

Kelford Inc. shows experts the way to always knowing what to say.